Lionfish (Pterois) are native to the Indo-Pacific region and have become invasive in the Mediterranean and Caribbean Seas, Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Seaboard of the US.

Lionfish (Pterois) are native to the Indo-Pacific region and have become invasive in the Mediterranean and Caribbean Seas, Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Seaboard of the US.

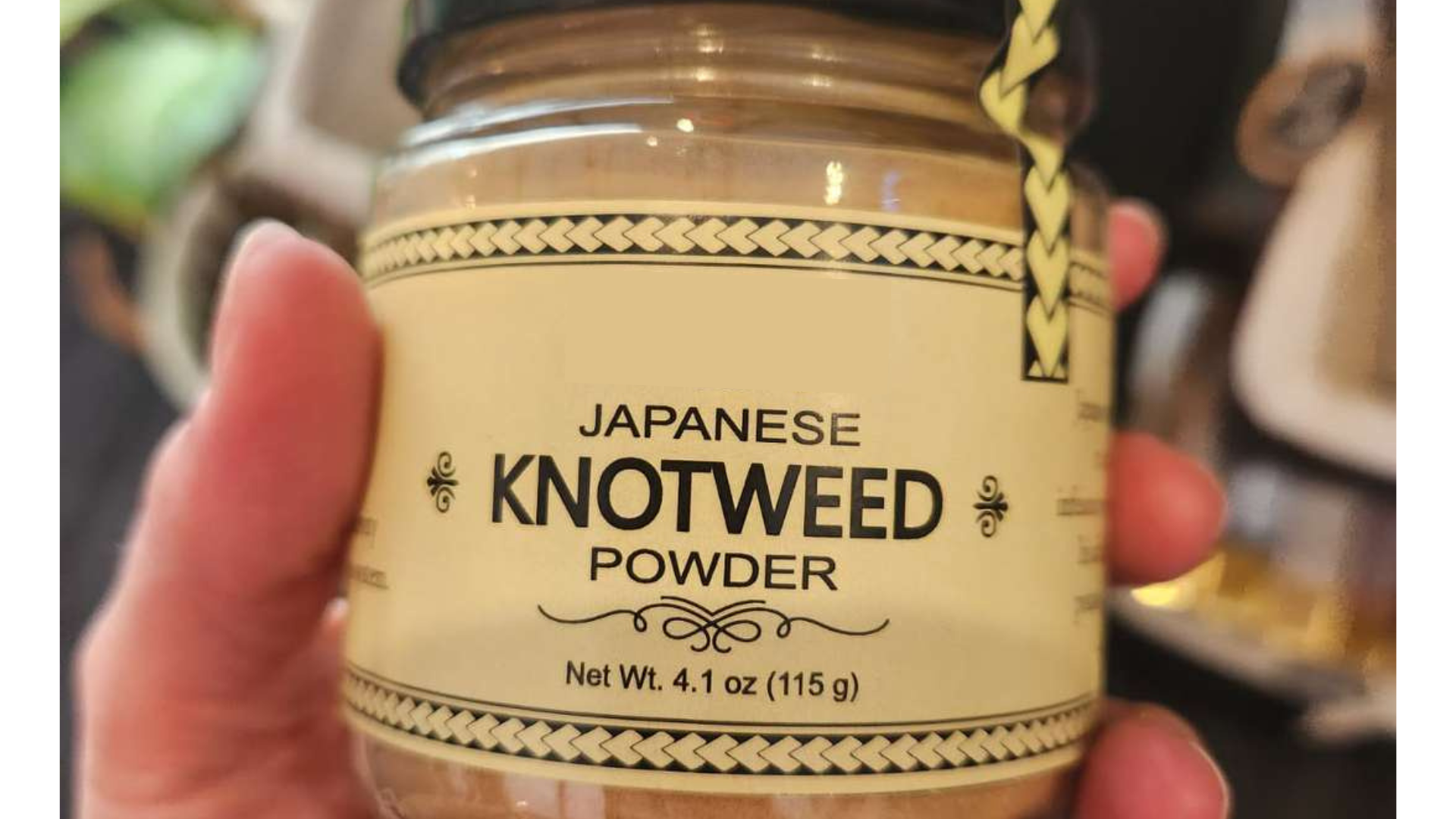

While travelling, I came across a jar that piqued my interest.

It contained some kind of powder for cooking and had the label “Japanese Knotweed”. Apparently, the dried and crushed Japanese knotweed powder can be added to drinks or smoothies for medicinal purposes. Who would have thought? I’ve only ever known knotweed to be an insufferably difficult to manage invasive weed. If we could consume all invasive species or turn them into commodities – like this Japanese knotweed powder – would that be a good solution to our invasive species problem? It turns out that the answer is more complicated than you’d think.

The idea of eating invasive species has gained a lot of traction recently as a way to control their populations. From lionfish ceviche and garlic mustard pesto, to wild boar sausage and green crab bisque, conservationists, chefs, and policymakers have explored whether putting invasive species on the menu could be a long-term solution.

On the surface, this approach seems like a win-win. Using invasive species for food could help keep their numbers in check while supporting local economies and providing a sustainable food source. However, it requires the same amount of planning and consideration as any other management tool. If not done properly, the results may be opposite the intended purpose.

Turning Lemons into Lemonade – Risks and Considerations

Despite its appeal, “Invasivorism” – the practice of eating invasive species – is not a guaranteed solution, and in some cases, it could do more harm than good. There are many biological, ecological, human health, and socio-economic factors that need to be considered when creating a market around the harvesting invasive species:

- Population Dynamics – How many individuals of a species need to be removed from a population every year for management to be successful? In the case of Lionfish, upwards of 65% of the population needs to be harvested every year for numbers to go down. For invasive plants, that number can be even higher.

- Species Dispersal – Does harvesting the species facilitate its spread to new areas? For invasive wild pigs, hunting is not recommended as it can cause populations to scatter into new areas and teach survivors to avoid future efforts.

- Ecosystem Health – Can you successfully harvest the species without negatively impacting the environment or native species? For example, native species populations may be harmed during harvest as a result of accidental bycatch.

- Human Health – Does encouraging the public to harvest an invasive species pose any risks to their health? Harvest or bounty programs should include guidance on proper techniques for capturing and handling the target species. For example, improper handling of lionfish’s venomous spines can cause significant injury.

A fisherman catches an invasive red lionfish.

A fisherman catches an invasive red lionfish.

One of the biggest risks is that demand could drive the opposite effect,

leading people to farm or illegally introduce invasive species to sustain supply. These unintended consequences are often referred to as the ‘Cobra Effect’. Coined after a failed management strategy in colonial India, when the British government placed a bounty on dead cobras. Citizens ended up breeding cobras to earn the reward. But once the government found out about the breeding activities the bounty program was scrapped, and all the now-“worthless” snakes were released. The result was a significant increase in the cobra population.

Another drawback is that the commercialization of invasive species, when successful, may create new socioeconomic problems. In Cozumel, Mexico, for example, fisheries were established that successfully reduced invasive lionfish numbers by 60% every year. But as populations declined, lionfish became scarce and eventually the markets collapsed. Even with the most careful planning, commercializing invasive species can still have unforeseen consequences.

So, Should We Eat Invasive Species?

It’s a complicated question, and the answer depends on the species, the region, and how harvesting is managed. When done carefully, eating invasive species can be an effective tool, especially for widespread species that lack natural predators.

Looking back at that jar of powdered Japanese knotweed I found, I should have asked myself:

- Was this harvested sustainably from its native ecosystem, or was it cultivated elsewhere?

- Was this knotweed intentionally grown outside its native range for sale, potentially increasing its spread?

- Is there any risk that processing, packaging, or transporting this product could lead to further introduction of the species?

- Does this product provide any meaningful contribution to controlling the species, or is it merely capitalizing on its presence?

- Am I unknowingly contributing to a cycle where demand incentivizes further spread rather than control?

I ended up leaving the jar on the shelf. What about you – would you eat an invasive species?